Efficiency and Ease at Sea November 9, 2021

It’s 10:30 on a Friday night and Research Assistant Erin Frates is getting ready to go to work.

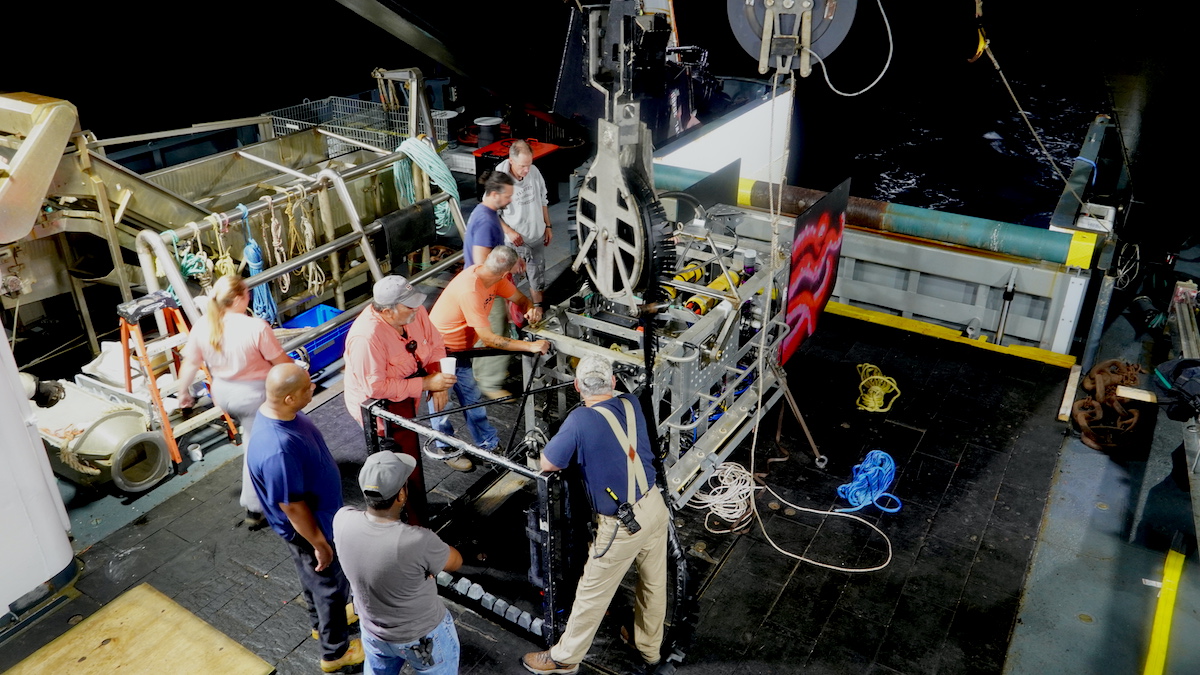

Standing on the aft deck of the E/V Nautilus, currently stationed a few miles west of the Channel Islands off the coast of California, Frates holds a line connected to Mesobot. The autonomous underwater robot has just returned from a six-hour dive in the Ocean Twilight Zone during which it captured dozens of environmental DNA (eDNA) samples.

Collecting eDNA is a relatively new (and robust) method for researchers to learn about the diversity and distribution of animal species in one of the hardest-to-reach areas of the ocean.

“With eDNA, we don’t have to catch an animal—we just need to cross paths with traces of material that they leave behind,” Frates says. “The sampler picks up evidence that they were in this particular area, and that gives us an idea of where different animals are at certain times.”

After the crane operator guides Mesobot out of the water and onto the deck, the team secures it. Frates detaches the hard plastic cartridges on its underside and carries them into the wet lab. There, she runs through a quick routine: disassemble each cartridge, dump out the water, label and seal the filters, and stick them in the freezer.

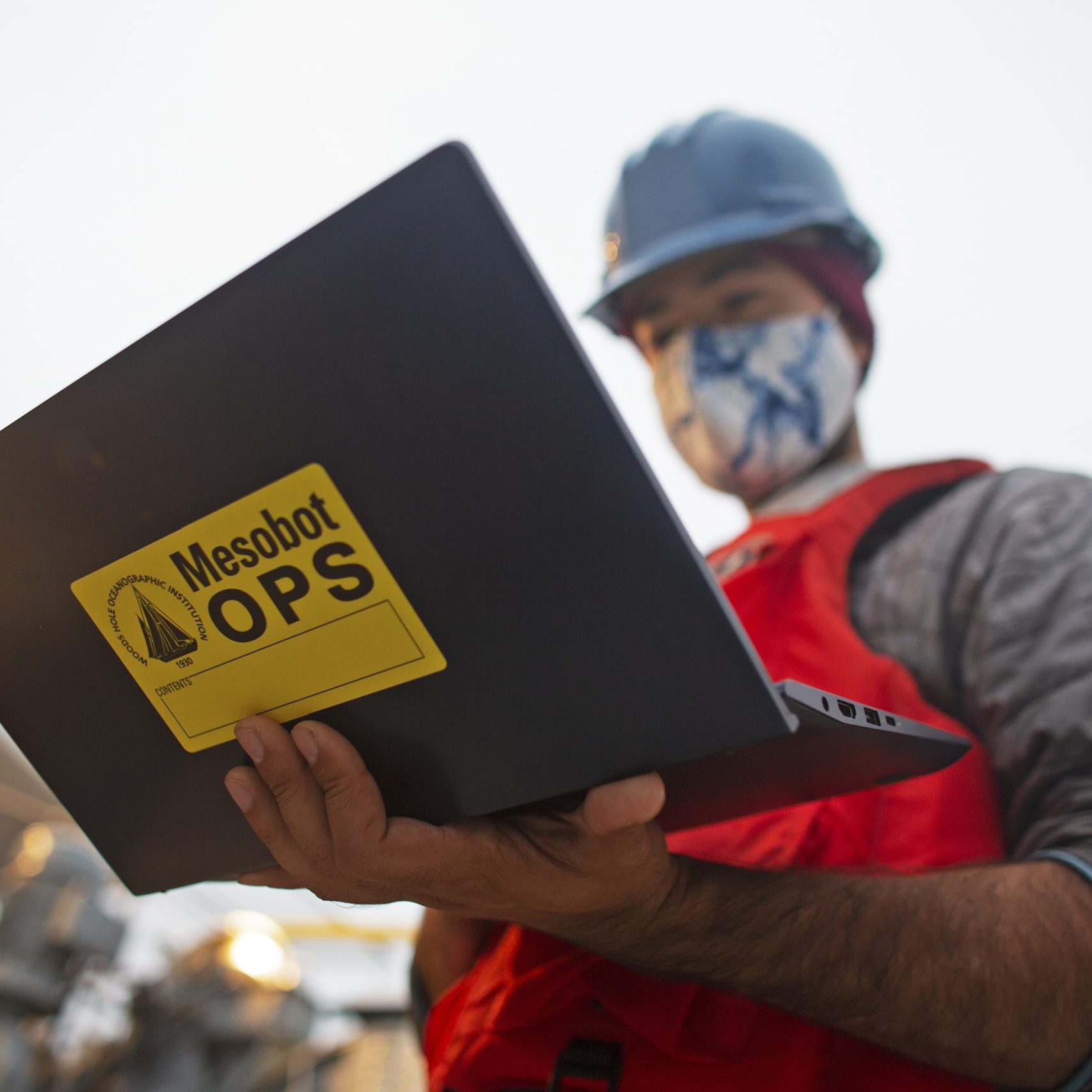

For Frates, this is her first time joining the Mesobot team. It’s also the first time she has processed samples at sea this quickly. Working alongside Lui Kawasumi, an engineer who helped build the sampler, the job of getting all the samples from the deck to the freezer is complete in less than an hour.

A big part of what makes the process so efficient is the sampler’s ability to filter the water it collects in situ.

“Getting samples filtered at depth is an exciting thing that I haven’t done before,” Frates says. “It makes me think differently about possible sampling strategies.”

Building on previous eDNA samplers, development of this iteration of multi-sampler was led by Kawasumi and Dr. Allan Adams. Its reusable cartridges are made from 3D printed materials that can collect up to 32 samples in a dive.

While on board the Nautilus, the Mesobot team stores the eDNA samples in a negative 80-degree Celsius freezer. At the end of the expedition, they will ship the samples back to WHOI where Dr. Annette Govindarajan leads the sequencing and data interpretation.

While the eDNA captured on the filters can provide a wealth of information (one sample can yield over 100,000 DNA sequences), Govindarajan says the additional data Mesobot collects is also critical.

“One of the great advantages of Mesobot is enabling the sampler to function alongside all the sensor data and radiometry that’s being collected,” she says. “We need those physical and environmental parameters to interpret the data.”

On this Nautilus cruise, the Mesobot team collects samples in 15-minute intervals, centered around sunset, to capture data from the evening migration of animals in the Twilight Zone.

During each dive, Dr. Dana Yoerger sits in the control room, keeping a close eye on the monitor displaying the EK80, which shows the movement of the biomass in the water. Thanks to the Nautilus live-streaming capability, Govindarajan and Adams can view the same screen from their homes in Massachusetts and coordinate directly with Yoerger on dive plans.

“I like that we’re collecting all of this data together,” Govindarajan says. “The sampler is highly efficient and Mesobot gives us a lot of flexibility to determine our experimental design. We’re really excited about the scientific possibilities that this approach enables.”