Casting a (long) line to the twilight zone food web February 20, 2023

By Elise Hugus

The sun was at half-mast over the horizon, blazing a trail of gold through choppy North Atlantic seas. The crew aboard F/V Monica had just finished dinner and were back on deck, clipping hooks onto a drum line as they traced the Northeast Continental Shelf, about 120 miles (193 km) offshore from Rhode Island. Setting 600 hooks on 30 miles (48 km) of longline was nothing new for the commercial fishermen, but the goal of this fishing expedition was different: catch swordfish, tuna, and sharks alive so the scientists on board could quickly tag and release them and learn more about their habits.

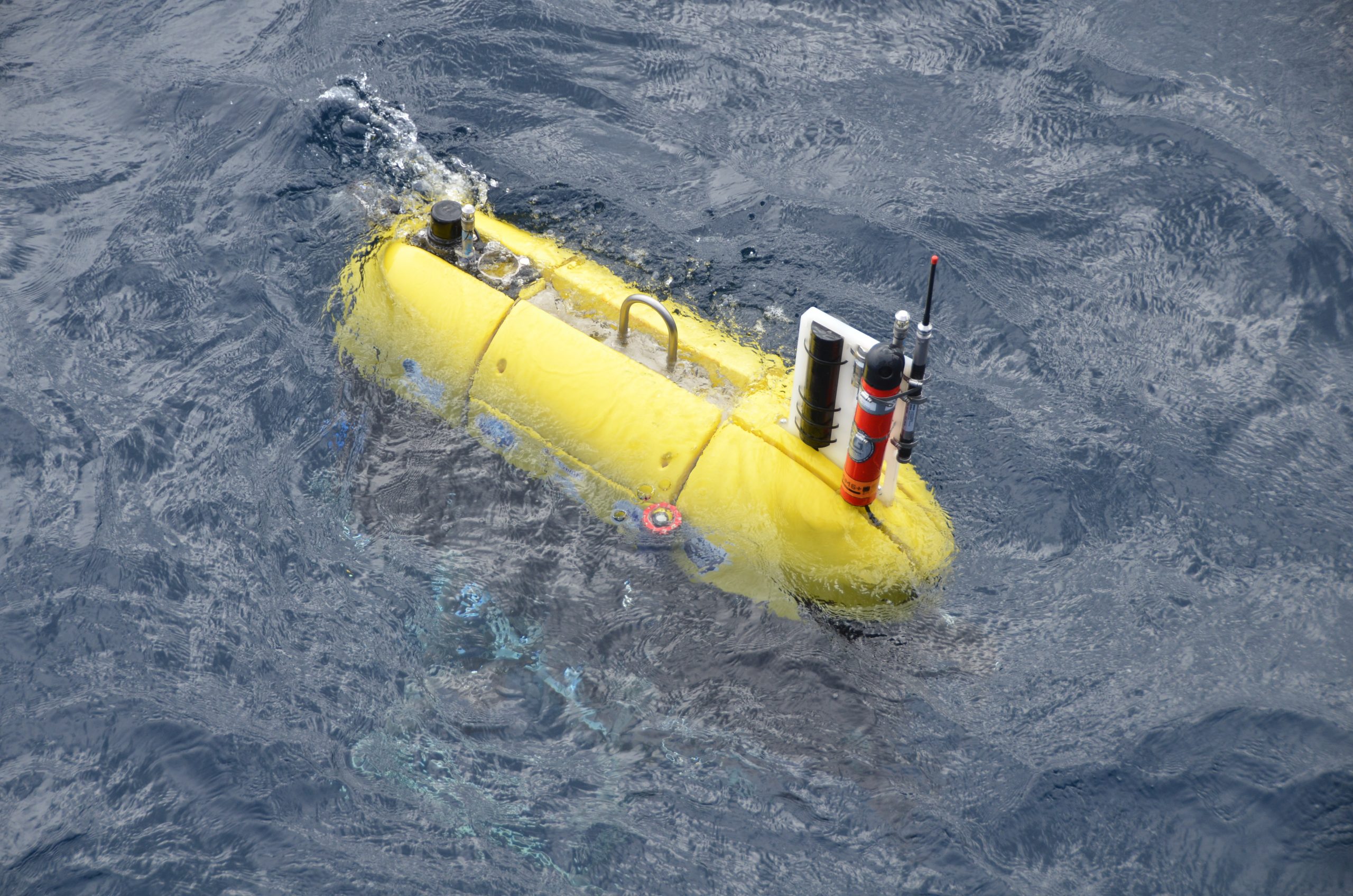

This unconventional fishing trip was part of a multi-vessel effort to study the mid-ocean “twilight zone”–from the tiniest traces of DNA to the largest marine predators–in a particular place and time. Gleaning insights from an arsenal of technologies, WHOI’s Ocean Twilight Zone Project scientists are building a layered snapshot of a region that supports the most marine life on Earth.

Through the cycles of eating and excreting, the twilight zone food web is responsible for transporting vast quantities of carbon from the surface to the deep ocean. Anything scientists can do to better understand its inner workings will help them refine the ocean’s capacity to store carbon–and recommend ways to sustainably harvest commercially important and emerging fisheries.

Aboard the longliner, the crew got a little shut-eye before getting up with the sun to reel in the night’s catch. As the sun crested the horizon, the scientists quickly assessed each fish and placed a tag on those found in good shape (others were released and the dead fish were kept for biological sampling). The big predators were outfitted with biologgers that collect oceanographic, behavioral and location data–and one lucky bigeye tuna and swordfish were tagged for the first time with a camera system that captures their movements from a fish-eye perspective. At the end of the two-week trip, the researchers had tagged one blue shark, six swordfish, five bigeye tuna, one yellowfin tuna, and one white marlin.