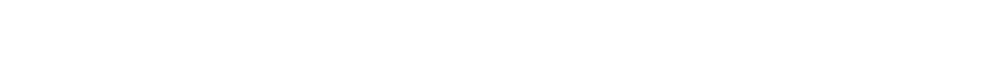

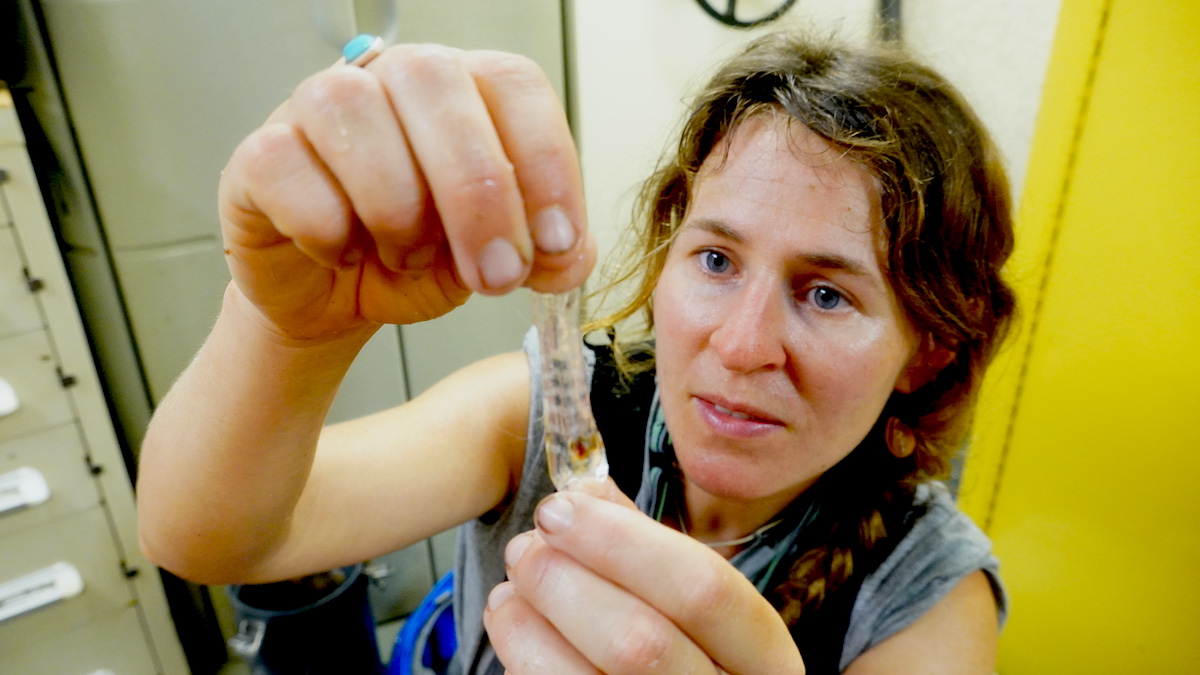

Spotlight: Heidi Sosik March 8, 2022

Heidi Sosik never intended to become an oceanographer. For her undergraduate degree, she studied civil engineering—but after being invited to come aboard a three-week research cruise in the north Atlantic, she found herself hooked. Today, Sosik studies plankton, the tiny organisms at the base of the marine food web, and has developed cutting-edge technology to document and categorize plankton species in seawater. In this interview, learn about her passion for the tiniest creatures in the ocean, the technologies she’s creating to study them, and much more.

When did you first realize that you wanted to work in oceanography?

I really wasn’t planning it. I grew up in a small town in Massachusetts with a modest background, and was working several jobs every summer, so it felt kind of momentous for me to be able to go to college. I decided I wanted to study civil engineering, since it would give me a good chance of getting a job afterwards. But I was also trying to take advantage of all the other opportunities available to me as an undergraduate. Somehow I got the message that I should try my hand at some research projects, and had an advisor that happened to be involved with studying marine plankton, so I tried doing research with her to see what it was like. My project ended up being a bit of a failure—all my lab experiments didn’t go according to plan, and I had to write this agonizing report. But it gave me a taste of what plankton are, how important they are to global health, and what it was like to work in a dynamic lab doing hands-on research. Near the start of my senior year, I was invited to volunteer on a research cruise, going from Woods Hole to the coast of north Africa. I had never done anything like it, and after that I totally fell in love with it. I pretty quickly decided to apply to graduate school in oceanography.

Throughout your career, you’ve done a lot of work developing new instruments to study plankton. How does your background in engineering shape your research?

Having studied civil engineering, my background wasn’t directly related to creating instruments—but it did give me an engineering mindset. It taught me problem solving approaches and quantitative approaches that I could bring to work in marine science. Today, I’m asking questions that are very ecologically grounded, but I’m also able to bring that quantitative technical side into the equation so I can do the science I’m so curious about. It’s a pretty good combination, really.

What keeps you passionate about studying plankton?

There are so many mysteries involved! I’m particularly interested in the way they interact with and influence everything in their environment, from light and nutrient levels to how the water itself around them moves. They’re incredibly impactful, but their small size also makes them really hard to study. I love that challenge—since you can’t see them with the naked eye, you need to rely on technology in order to figure out how they work. In some cases, you can collect them in nets and buckets, but many of them are fragile and easily damaged, so we need to create new ways to image them in their natural habitat. Doing that lets us see them in fine detail in their own environment, and identify not only what species they are, but what they’re doing to the water around them. The fact that there are technical challenges as well as scientific riddles makes it fun.

Why is it so important to study life in the twilight zone right now?

As humans, we have a pretty solid track record of overexploiting natural resources, to the point where we cause damage that we never intended to cause. Oftentimes, it’s because we just don't understand how a certain ecosystem works, or how interconnected it is with the rest of the planet. The twilight zone, however, is really hard to reach, which means that human impact on it is limited for the moment—but that could change in the next few years.

With this project, we have an opportunity to get ahead of any future impacts. We have a chance to understand how the zone is interconnected with the rest of the ocean; how life there helps regulate global carbon and climate; how it supports the food web all the way up to top predators. The more we learn, the more we realize that the twilight zone provides incredible services to the whole planet, and we want to protect that value so we can be better stewards of the oceans moving forward. It’s easier said than done, but I’m excited that we can have that sort of impact.

What are some of the biggest surprises you’ve encountered while studying the ocean twilight zone?

A few years ago, I had an opportunity to personally travel into the twilight zone aboard a submersible vehicle. Normally, we use a lot of remote technology to study the zone, and human-occupied submarines aren’t part of our toolset to push that knowledge forward—so when I went, I thought it would just sort of be a cool experience, but wasn’t expecting much research payoff. Once we were down there, though, I was blown away. I was able to get a firsthand impression of marine snow, which is made up of tiny clumps of organic matter that sink through the water, and see for myself its role in the ecosystem. Now, marine snow is something I’ve known about since I first started studying ocean life in school. It’s something that has been a part of my research on some level for my entire career. It’s everywhere in the ocean. But seeing it from a submarine, experiencing the way it dominated my visual field, really changed my perspective. I have a whole new appreciation of this stuff that is so critical to how the twilight zone ecosystem works. It was burned into my brain. It really surprised me how much that experience has stuck with me and made me think about life in the twilight zone in a different way.

What do you do when you’re not studying the oceans?

I love baking bread. I’m pretty obsessive about it—I even grind my own flour. I’m part of an annual share in a grain co-op, which is all grown locally here in New England, and get an annual delivery of 50 pounds of grain that I process with an industrial mill in the corner of my living room. I’ve got a sourdough culture I grew 20 years ago, and it’s still going strong. For me, I think it’s a great example of how important microscopic life is to the world. In the oceans, life wouldn’t exist without plankton—they make much of the oxygen available on Earth, and they feed almost all of the other marine animals we humans rely on for food. Even in your own kitchen, you can’t make something as basic as a loaf of bread without microbes. It’s a constant reminder that we’re really just a small part of a much larger global ecosystem.

Clockwise from top: home-ground whole wheat brioche rolls, sourdough, chocolate babka, and seeded bagels. (Photos courtesy Heidi Sosik)