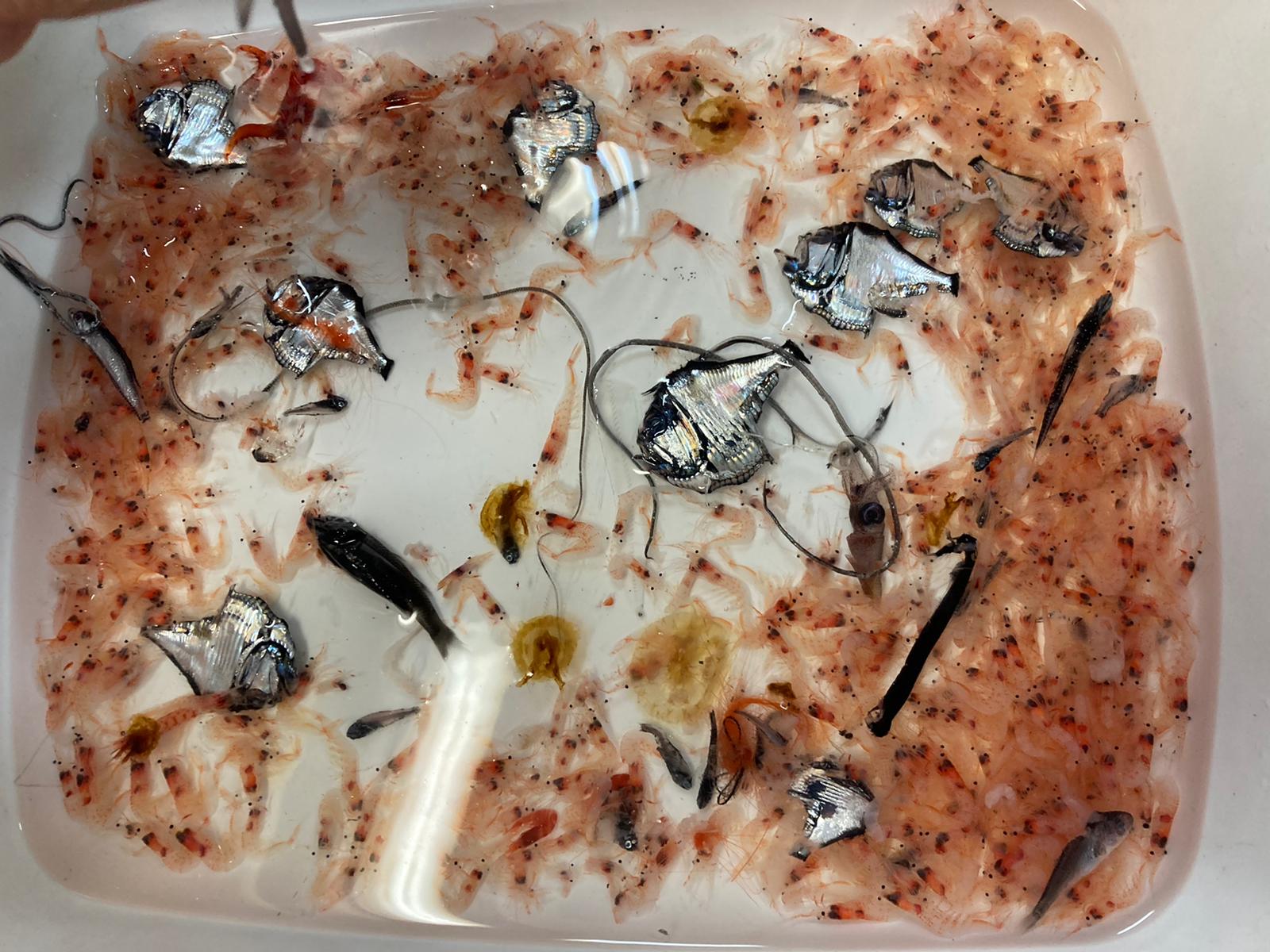

Spotlight: Katy Baker September 16, 2022

Katherine “Katy” Baker is a PhD. student at the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies at the University of Tasmania, Australia. She studies how carbon is exported from the sea surface to the deep ocean through the vertical migration of twilight zone animals in the Southern Ocean. Her research involves sampling at sea and a series of lab experiments.

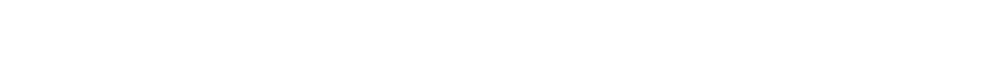

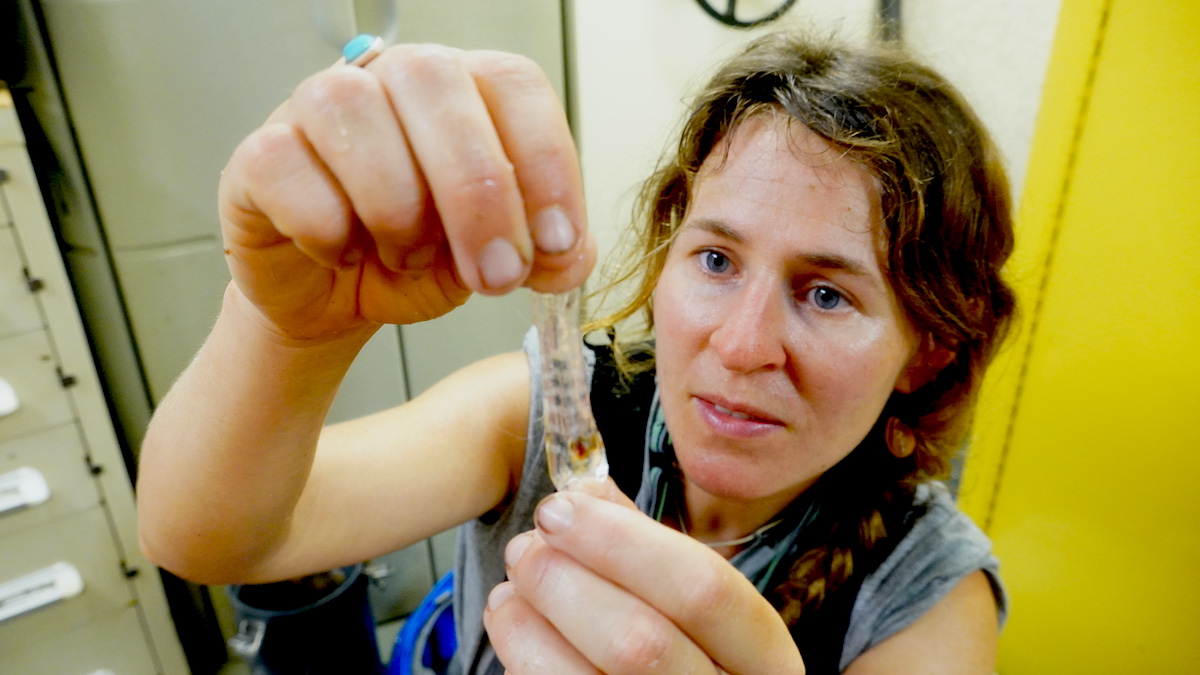

During an OTZ research cruise in August 2022, Baker worked with the MOCNESS team to gather creatures pulled up from hundreds of meters below the surface. If any were still wriggling around in the nets, she would race to measure their respiration levels before they perished.

As the cruise wound down, Baker shared how she connects her research in the southeastern hemisphere to what’s happening in the northwestern!

-Andrea Vale, OTZ field correspondent

Can you explain your research in five words?

How OTZ animals export carbon.

What brought you aboard the Bigelow? How many research cruises have you been on so far, and how does this one differ from the others?

My project is affiliated with the Joint Exploration of the Twilight Zone Network (JETZON), a UN Ocean Decade Program connecting ocean twilight zone studies around the world. I was connected to WHOI’s OTZ project through a JETZON colleague, Helena McMonagle, who is also studying active carbon export. I was visiting family in the U.S. this summer, so we thought it would be a great opportunity to collaborate on this cruise. We’re attempting to measure respiration rates of mesopelagic fishes. If the method works, I aim to replicate the experiment in the Southern Ocean, with the hopes of comparing these data across oceans.

This is my third oceanographic research cruise. Since my research is focused on the Southern Ocean, voyages tend to be longer (more like six weeks), colder, and we often experience rough seas. During this cruise, we've had beautiful weather and I have enjoyed wearing shorts on deck. I have also been enjoying the smorgasbord of American snacks that I’ve been missing for years!

What are some differences between researching in the Southern Ocean and the Atlantic? How do the two sides of the world connect?

As soon as you plunge beyond 200 meters anywhere in the world, you will find yourself in the ocean twilight zone. Here in the northwest Atlantic, it has been fascinating to see the similarities in the community composition of migrating animals we’re seeing on this cruise, compared to what I study in the Southern Ocean!

What do you want people to understand about the Ocean Twilight Zone?

Through my research, I hope to shed light on the role that twilight zone animals play in the carbon cycle. By consuming carbon-rich phytoplankton (microscopic plants) and primary consumers at the sea surface at night, and respiring, pooing, and dying at their resident depths in the ocean twilight zone during the day, these animals transport carbon to the deep sea, where it has the potential to be sequestered for hundreds of years.

What are your daily tasks and responsibilities on the ship?

I am trialing an experiment on this cruise to get a better understanding of mesopelagic fish respiration. Before each net is hauled back on deck, I set up equipment to measure the amount of dissolved oxygen in seawater and prepare buckets to hold live fish. If we get live ones, I set them up in little aquariums and measure the amount of oxygen they take up. If we don’t end up with live fish, I help the MOCNESS team process zooplankton samples from each trawl.

What are your biggest challenges while conducting research at sea?

The sea provides a unique set of challenges for scientists. Good weather is an important component of successful instrument deployments, but we often find ourselves working in sub-optimal conditions. Sometimes our science program can be delayed for days as we wait for calmer weather.

What is the most rewarding or fulfilling part of doing science at sea?

I love connecting with other scientists at sea and learning about their research. We are all attempting to answer the same questions, but from different angles. Everyone’s science is an important piece to the puzzle, but it’s easy to forget this when I am working in the office. There’s no better place to witness the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration than out at sea.

What are some things you pack for a research cruise that might surprise people?

A yoga mat–stretching at sea is important and the view is hard to beat!